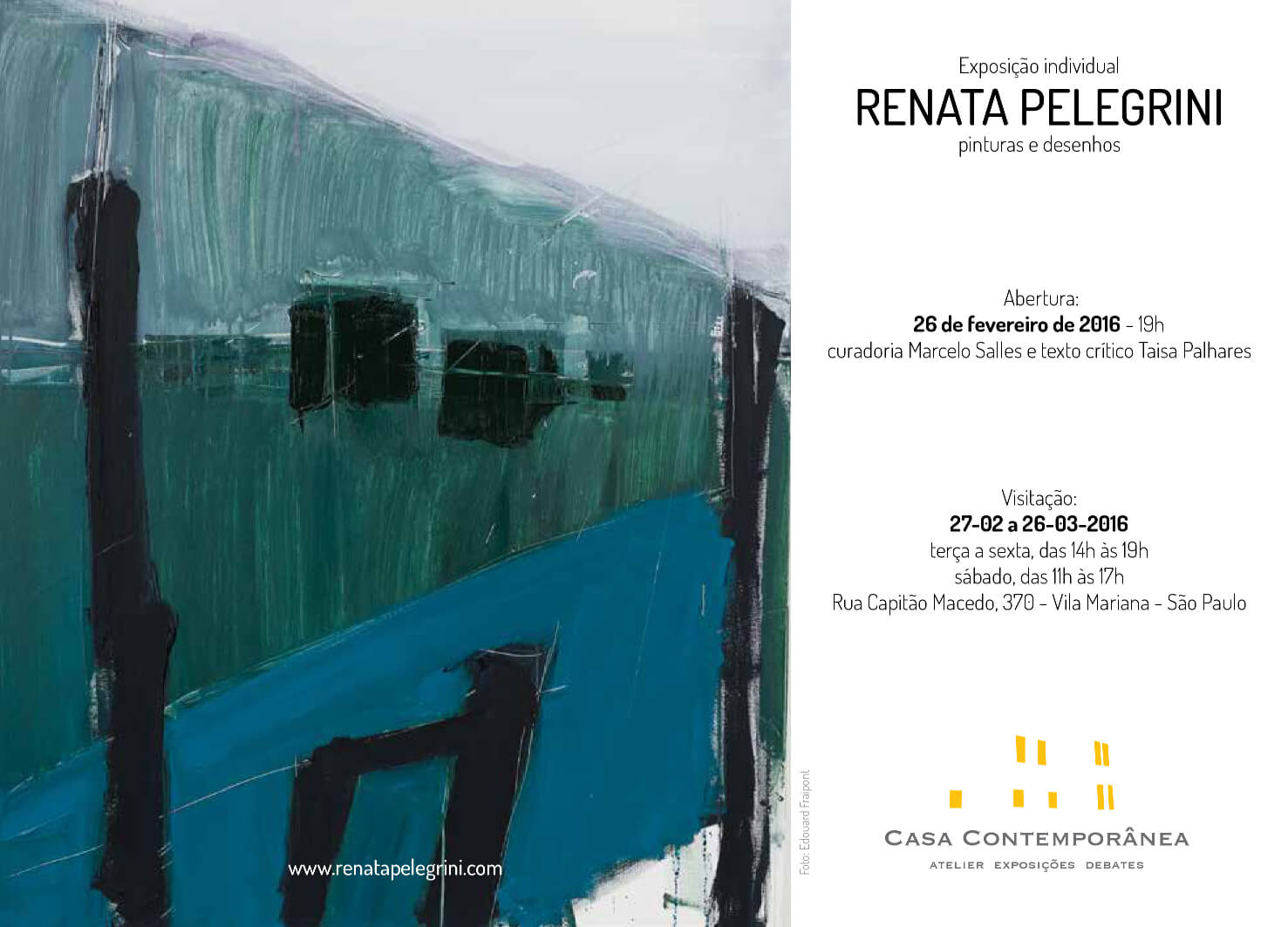

Exposições

Renata Pelegrini

Renata Pelegrini: desenho e pintura.

O livro “Cidades Invisíveis “, de Ítalo Calvino, nos traz a narrativa do comerciante/embaixador Marco Polo ao poderoso conquistador Kublai Khan sobre cidades pelas quais passou em suas viagens pelo vasto império do Khan. Calvino apresenta descrições de cidades inverossímeis compostas por experiências as mais diversas, da literatura das Mil e Uma Noites ao cinema, de viagens e de cidades reais (até onde Veneza pode ser real…), construídas pelas palavras de Marco Polo e reconstruídas por seu ouvinte, Kublai Khan.

…

O tempo em que vivemos, a contemporaneidade, parece não ter uma convivência consensual com linguagens mais tradicionais nas artes visuais, tais como desenho e pintura. Mesmo assim artistas continuam optando por elas. Alguns produzindo trabalhos mais assimiláveis, com um ou outro elemento capazes de provocar estranhamento; se valem da paródia ou do cinismo em relação ao fazer e são trabalhos eminentemente visuais, diretos em sua apreensão. Outros fazem a opção, ainda que neste caso seja menos uma opção do que uma necessidade interior ou coerência com a maneira de pensar, por trabalhos que necessitam um tempo mais lento para sua assimilação, tempo este que não temos mais.

Este segundo grupo possui [1] um comprometimento com sua produção muito forte, respeitoso até, principalmente em relação a pintura. Há uma filiação, em maior ou menor grau, desses artistas à características do que se convencionou denominar modernismo, tais como uma certa autonomia do objeto de arte e a evidência autoral, mas desprovidos de um sentido épico ou grandioso; um desencanto realista, como convém ao presente.

Quanto aos trabalhos de Renata Pelegrini podemos associar também uma visceral expressividade. Desta maneira eles demandam do espectador um retirar-se do mundo para nos voltarmos ao que nos pertence, aquilo que nos forma enquanto experiências vivenciadas.

…

Normalmente a pintura é considerada um trabalho mais elaborado do que o desenho, até mesmo pelos artistas, onde muitas vezes o segundo, configurado no suporte papel, aparece como um estudo, um esboço a ser melhorado na pintura. Não é o que acontece nesta produção. Há uma autonomia entre ambas as linguagens; elas se alimentam, se equivalem ao lidar com o motivo escolhido, guardando as especificidades pertinentes a cada linguagem.

Tanto os desenhos como as pinturas são de difícil classificação, paradoxalmente porque Renata tem uma atitude mais afeita à contemporaneidade quanto às múltiplas influências e referências que possui. Vão de Paulo Pasta a Iberê Camargo, de De Kooning a Sean Scully, de Richard Serra a Giacometti, de Albert Oehlen a William Kentridge, de Diebenkorn a Eduardo Stupia, de Rosemarie Trockel a Julie Mehretu, sem esquecer suas muitas referências literárias onde Fernando Pessoa é a mais forte. Esta diversidade acaba por deixar os trabalhos aos olhos do público sem uma “ancoragem” por semelhança. Além disso, Renata escolheu, ou foi levada a isto, uma abordagem mais arriscada do motivo principal de seus trabalhos que é o espaço circundante, em maior ou menor escala; este risco reside na indefinição entre o reconhecível e o não reconhecível.

Formalmente, tanto nos desenhos como nas pinturas, surgem elementos que estão mais próximos do léxico moderno, mas devido à sua particular abordagem trazem uma atualização contemporânea para os trabalhos.

O primeiro é o uso da perspectiva, mas que apenas alude a perspectiva correta ou geométrica. Ela ora se decompõe em vários planos incongruentes questionando a planaridade do trabalho ou se contrapõe ao espaço estabelecido através do uso de planos de cor. Esta concepção cria um dinamismo reforçado pelo segundo elemento, a saber, as linhas. Estas linhas não são, porém, linhas de contorno ou de limites a serem preenchidos e nem estão a serviço da perspectiva; sua utilização em alguns trabalhos desestabiliza o conjunto. Elas são linhas de força. Intensas, abertas. Além dos aspectos formais há outro que podemos associar a fenomenologia e também à memória: o “genius loci”. Este termo, apropriado da arquitetura, refere-se ao “espírito do lugar” e está associado à compreensão do que não é visível nos espaços . Em seu processo de produção, Renata utiliza espaços que sofrem a alteração para o que se denomina

lugar. São esses lugares, seja em pequena escala e próximos ou amplos e distantes, que ela fotografa ao visitá-los ou através de imagens de outros olhares que ela reelabora em sua memória, nas impressões e experiências vivenciados, em contato com eles.

…

Tal qual Marco Polo, Renata Pelegrini descreve seus lugares e os compartilha conosco. A origem desses lugares é específica mas, no processo de nos mostrar o que está além de pilares, lajes, pátios, mares ou paisagens, eles tornam-se todos os lugares e também nenhum. É preciso que eles se reconstruam novamente em quem os vê.

Parafraseando Calvino (ou Marco Polo), tanto artista quanto espectador acreditam que desenhos e pinturas são obras da mente ou do acaso, mas nem um nem outro são capazes de sustentar pigmentos, linhas, composições colocadas em um suporte bidimensional. De obras de arte não aproveitamos suas belezas visíveis ou compreensíveis, mas as respostas que dão as nossas perguntas. Ou os questionamentos que nos deixam.

Marcelo Salles

[1] Este grupo , heterogêneo e nada pequeno, é composto por artistas jovens como André Ricardo e Felipe Goés ou com trajetória mais longa como Antônio Malta e Helena Carvalhosa, entre outros.

O enigma da janela

Um dos quadros mais icônicos da pintura do século 20, e que se mantém enigmático até hoje, é a tela Porte-fenêtre à Collioure (1914), de Henri Matisse. A composição, em tons de azulado, verde, cinza, mas predominante preto, coloca-se entre a representação e a não-representação de um espaço conhecido, vagamente explicado pelo título, sintetizando a relação do artista com a abstração, à qual ele nunca aderiu efetivamente. Assim como em outros trabalhos do pintor francês, desenho e cor vivem em harmonia, ou seja, não há a predominância de um sobre o outro, posto que o objetivo é superar a dicotomia que domina a história da pintura desde o Renascimento.

Nota-se que o preto sintetiza essa relação, na medida em que é tanto linha quanto cor. Aliás, ele é o centro da composição, aquilo que “vemos” no interior (ou seria exterior?) da janela, o local onde nosso olhar se fixa, emanando uma luminosidade que ressoa por todo o quadro. Como se sabe, Matisse, o maior colorista da arte moderna, foi também o pintor que mais soube explorar o preto enquanto cor – emanação de luz – realizando uma série de pinturas na qual esse tom tem um papel central. Se é certo que esse quadro faz uma referência direta à outra pintura magistral da arte francesa, Le Balcon (1868) de Manet, ele surpreende pela completa ausência de narrativa. O que predomina é quase um sentimento de suspensão de qualquer ação, e o jogo entre a claridade das cores quase transparentes e a luz negra. É um arcano da pintura de todos os tempos, o que abriu à arte novos caminhos.

A meu ver, a produção de Renata Pelegrini filia-se diretamente a essa tradição da pintura moderna que hoje está sendo ricamente retomada por vários pintores contemporâneos. De uma forma que é muito mais visual do que intelectual, no sentido que não se trata de pensar conceitualmente a pintura, como muitos artistas fizeram depois de 1960. Mas repensar suas questões a partir do próprio fazer. Por isso sua produção relativamente recente, cuja pesquisa se inicia no desenho, levando para as telas uma qualidade gráfica marcante, apresenta uma enorme coerência.

Seus desenhos, realizados em carvão, sanguínea, grafite e giz, já trazem a ambiguidade espacial que marcará o uso do preto como cor: ora são linhas que estruturam os espaços, ora são manchas, muitas vezes alcançadas pelo gesto de apagamento. Neles há um equilíbrio espacial entre o lugar reconhecível e a abstração, mas também entre o peso e a luz do preto que magnetiza o olhar e a experiência da leveza por meio das zonas esmaecidades de cores transparentes.

No caso de suas telas, o preto permanece uma potência de luz que serve como imã da composição, entretanto convivendo com tonalidades tão fortes quanto ele: azul, amarelo, ocre, verde, cinza, terracota, vermelho, rosa, entre outras. Se por um lado a construção do espaço parece mais evidente (e muitas vezes a artista parte da observação de fotografias), a composição nunca é exatamente fechada ou plenamente reconhecível. Predomina um jogo entre o movimento de traços em diagonal, como a sugerir o ponto de fuga, mas que de certa maneira é constantemente tensionado por formas ou massas de cor quase abstratas. O que se tem é o equilíbrio provisório, acentuado pela exploração de elementos que sugerem o inacabado, como o escorrimento de tinta ou a evidência gestual das pinceladas.

O mundo não tão sereno das pinturas de Renata Pelegrini é muitas vezes atravessado por um fino traço quase imperceptível, realizado com um objeto pontiagudo que risca a superfície da tela. Na composição, esses traços tornam-se protagonistas de novas direções para o nosso olhar. Na verdade, são linhas de força que desestabilizam o reconhecimento instântaneo do que seria uma imagem do real. Neste sentido, contribuem para sensação de construção e descontrução do espaço, e consequentemente de nossa relação com ele, que é uma das qualidades centrais de seu trabalho. Lembra-nos que a arte que importa, seja pictórica ou não, é sempre um enigma.

Taisa Palhares

Renata Pelegrini: drawings and paintings

The book “Invisible Cities” by Italo Calvino brings us the narrative, addressed by merchant/ambassador Marco Polo to powerful conqueror Kublai Khan, describing the cities which he passed on his travels throughout the Khan’s vast empire. Calvino presents us with descriptions of unbelievable cities composed of the most diverse experiences, from the literature of the One Thousand and One Nights to cinema, as well as real travels and cities (to the extent that Venice can be called real…), constructed by the words of Marco Polo and reconstructed by his listener, Kublai Khan.

…

The time we live in, the contemporary, does not appear to coexist consensually with more traditional languages in the visual arts, such as drawing and painting. Even so, artists continue to adopt them. Some produce more easily-assimilated work, with one or the other element capable of generating strangeness; they make use of parody or cynicism with respect to craft, and make eminently visual, directly apprehensible works. Others choose – even though, in this case, it is less an option than an inner need, or a correspondence with a manner of thinking – to make works that require a slower time in which to be assimilated, time which we no longer have.

This second group [i] is deeply committed to its work, reverent even, especially with respect to painting. These artists subscribe, to a greater or lesser extent, to the characteristics of what is conventionally called modernism, such as a degree of autonomy of the art object and the presence of manifest signs of authorship, but they lack a sense of the epic or the grandiose; they display a realist disenchantment, as befits the present.

To the works of Renata Pelegrini we can also associate a degree of visceral expressiveness. In this manner they demand from the viewer a withdrawal from the world and a turn towards what belongs to us, that which forms us as lived experience.

…

Painting is usually considered more elaborate than drawing, even by artists, for whom the latter often manifests as a study, limited to its paper support, a sketch to be improved upon in the painting. That is not what happens with this body of work. Each language is autonomous; they feed off each other, and are equals in dealing with the chosen subject, maintaining the specificities pertinent to each.

Both the drawings and the paintings here are difficult to classify, paradoxically because Renata’s approach is closer to contemporary as far as her multiple influences and references. These range from Paulo Pasta to Iberê Camargo, from de Kooning to Sean Scully, from Richard Serra to Giacometti, from Albert Oehlen to William Kentridge, from Richard Diebenkorn to Eduardo Stupia, from Rosemarie Trockel to Julie Mehretu, without forgetting her many literary references, the strongest of which is Fernando Pessoa. Because of this diversity, the works present themselves to the public eye without an “anchor” of similarity. Furthermore, Renata chose, or was made to choose, a riskier approach to the main subject of her work, which is, to a greater or lesser extent, surrounding space; this risk resides in the indefiniteness manifest between the recognizable and the non-recognizable.

Formally, in both the drawings and paintings, elements emerge that seem closer to the modern lexicon, but which, because of the manner in which they are approached, result in a contemporary updating of the work.

First is the use of perspective, which nevertheless only alludes to correct or geometric perspective. Here it decomposes into various incongruous planes, questioning the flatness of the work; there it offsets established space through the use of color planes. This conception creates a dynamism reinforced by the second element, the lines. These lines are not, however, contour lines or limits to be filled, nor are they at the service of perspective; in some works, their use destabilizes the whole. They are power lines; intense, open. In addition to the formal aspects, there is another that we can associate with phenomenology, and also memory: the “genius loci.” This term, appropriated from architecture, refers to the “spirit of place,” and is associated with the capture of what is not visible in the spaces. In her work process, Renata uses spaces that suffer transformation into what are called places. It is these places, whether small scale and close, or large and distant, that she photographs by visiting, either through images from other gazes reworked in her memory, or through direct impressions and experiences.

…

Like Marco Polo, Renata Pelegrini describes her places and shares them with us. The origin of these places is specific but, in the process of showing us what lies beyond pillars, slabs, patios, seas or landscapes, they become everyplace and, also, no place. They need to be rebuilt again in those who see them.

To paraphrase Calvino (or Marco Polo), both artist and viewer believe that drawings and paintings are works of the mind or of randomness, but neither of these is able to bear pigments, lines, and compositions on a two-dimensional support. From works of art we derive not their visible or comprehensible beauties but, rather, the answers they provide to our questions. Or the questions they leave us.

Marcelo Salles

[i] This group, heterogeneous and hardly small, consists of young artists like André Ricardo and Felipe Goes, as well as some with longer careers, like Antônio Malta and Helena Carvalhosa, among others.

The Enigma of the Window

One of the most iconic pictures of 20th century painting, one that remains enigmatic to this day, is the canvas Porte-fenêtre à Collioure (1914) by Henri Matisse. The composition, in shades of blue, green, and gray, but predominantly black, lies between non-representation and the representation of a known space, vaguely explained by its title, and synthesizes the artist’s relationship with abstraction, which he never effectively adopted. As in other works by this French painter, drawing and color live in harmony; that is, neither dominates the other, since the objective is to overcome the dichotomy that had dominated the history of painting since the Renaissance.

Witness how black encapsulates this relationship, to the extent that it is both line and color. In fact, it is the center of the composition, that which we see inside (or would it be outside?) the window, the place where our gaze becomes fixed, emanating a luminosity that resonates throughout the picture. As is known, Matisse, the greatest colorist of modern art, was also the painter who best knew how to exploit black as a color – as emanation of light –, executing a series of paintings in which that tonality plays a central role. If it is certain that this picture refers directly to another masterful painting of French art, Manet’s Le Balcon (1868), it surprises us by its complete absence of narrative. What prevails is a sense of the quasi-suspension of any action, as well as the play between the clarity of the almost transparent colors and the black light. It is one of the great mysteries of painting, one that opened new paths for art.

In my view, Renata Pelegrini’s work is directly affiliated with this tradition of modern painting, one that is today being richly revisited by many contemporary practitioners. But in a manner that is much more visual than intellectual, in the sense that it is not about thinking conceptually about painting, as did the work of many artists after 1960. Rather, it is a rethinking of its own issues on the basis of practice itself. For this reason, her relatively recent production – whose research begins in drawing, bringing to the canvases a striking graphic quality – demonstrates enormous coherence.

Her drawings, executed with charcoal, sanguine, graphite and chalk, already bear the spatial ambiguity that will mark her use of black as a color: here they are lines that structure the spaces, there they are stains, often achieved by a gesture of erasure. There is a spatial equilibrium here between abstraction and recognition of place, but also between the luminosity and weight of a black that magnetizes the gaze and the experience of lightness through washed-out areas of transparent colors.

In the case of her canvases, black remains a beacon of light that serves as a compositional magnet, nevertheless coexisting with equally strong tonalities: blue, yellow, ocher, green, gray, terracotta, red, and pink, among others. If, on one hand, the construction of space appears more evident here (and the artist often uses photographs as her starting point), the composition is never quite closed or clearly recognizable. The movement of diagonal strokes is the dominant play, hinting at a vanishing point, but one constantly offset by nearly abstract forms or masses of color. What we have here is a provisional equilibrium, heightened by the exploration of elements that suggest the unfinished, like the dripping of paint, or the gestural evidence of brushstrokes.

The not-so-serene world of Renata Pelegrini’s paintings is often crossed by a thin line, nearly imperceptible, made with a sharp object that scrapes the canvas surface. In the composition, these lines point the gaze at new directions. In truth, they are lines of power that destabilize the instantaneous recognition of what would be an image of the real. In this manner, they contribute to a sense of construction and deconstruction of space, and consequently of our relationship with it, one of the central qualities of her work. It reminds us that art that matters, whether pictorial or not, is always an enigma.

Taisa Palhares

Biografia

Nascida em São Paulo em 1967, Renata Pelegrini estudou na Universidade de São Paulo. Possui bacharelado em Letras e licenciatura em Educação.

Residiu todo o ano de 1995 em Nova Iorque, onde iniciou seus estudos de caligrafia. Durante os dois anos de 2006 e 2007 morou na Itália, onde expandiu sua prática expressiva com aulas na Associação Caligráfica Italiana em Milão e em Lugano, na Suíça, estudando diretamente com artistas.

De volta ao Brasil, diplomou-se em Artes Plásticas na Escola Panamericana de Artes de São Paulo.

A partir de 2010 expõe regularmente sua produção: seleção para o MAM Campinas e para a Galeria Belvedere Paraty. Coletivas na Galeria Área Artis, na Escola Panamericana de Artes, no Instituto Tomie Ohtake – Grupo Paulo Pasta e no Salão de Arte Contemporânea de Piracicaba.

Em 2015 suas obras foram selecionadas para o Salão Nacional de Arte de Jataí, o Salão de Arte de Ribeirão Preto Nacional Contemporâneo, o Salão de arte Contemporânea de Piracicaba e para o Salão de Arte Contemporânea de Guarulhos. Ainda nesse ano, participa de coletiva na Casa Contemporânea.

Uma de suas pinturas hoje compõe a coleção de Luciano Benetton na Itália para projeto o Imago Mundi.

Atualmente Renata trabalha com pintura e desenho em São Paulo, onde tem seu estúdio. Integra o grupo Pigmento de artistas.

Born in São Paulo in 1967, Renata Pelegrini studied at Universidade de São Paulo, where she got her B.A. in Language Teaching and her B.A. in Education.

In 1995 she lived the entire year in New York, where she began her calligraphy studies. During the two years of 2006 and 2007 she lived in Italy and studied at the Associazione Caligrafica Italiana (Italian Calligraphy Association). Both in Milan and in Lugano – Switzerland – she widened her artistic interests by having classes directly with the Association´s artists.

Back in Brazil, Renata got her B.F.A. at Escola Panamericana de Artes in São Paulo.

As of 2010 she has regularly exhibited her work in and out of São Paulo: selected works at MAM Campinas and at Galeria Belvedere Paraty; collective exhibitions at Área Artis Galeria, Escola Panamericana de Artes de SãoPaulo, at Instituto Tomie Ohtake with the Paulo Pasta group of students and at the Piracicaba Contemporary Art Exhibit.

In 2015 her artwork was selected to the Jataí National Art Exhibit in Goiás, to the National Contemporary Art Exhibit of Ribeirão Preto (SARP), to the Contemporary Art exhibit of Piracicaba (SAC) and to the Guarulhos Contemporary Art exhibit. At Casa Contemporânea, she took part in a collective exhibit.

One of her paintings is now part of the Luciano Benetton collection in Italy for the Imago Mundi project.

At present Renata works with painting and drawing in São Paulo, where she has her studio. She is one of the members of Pigmento – a group of artists.